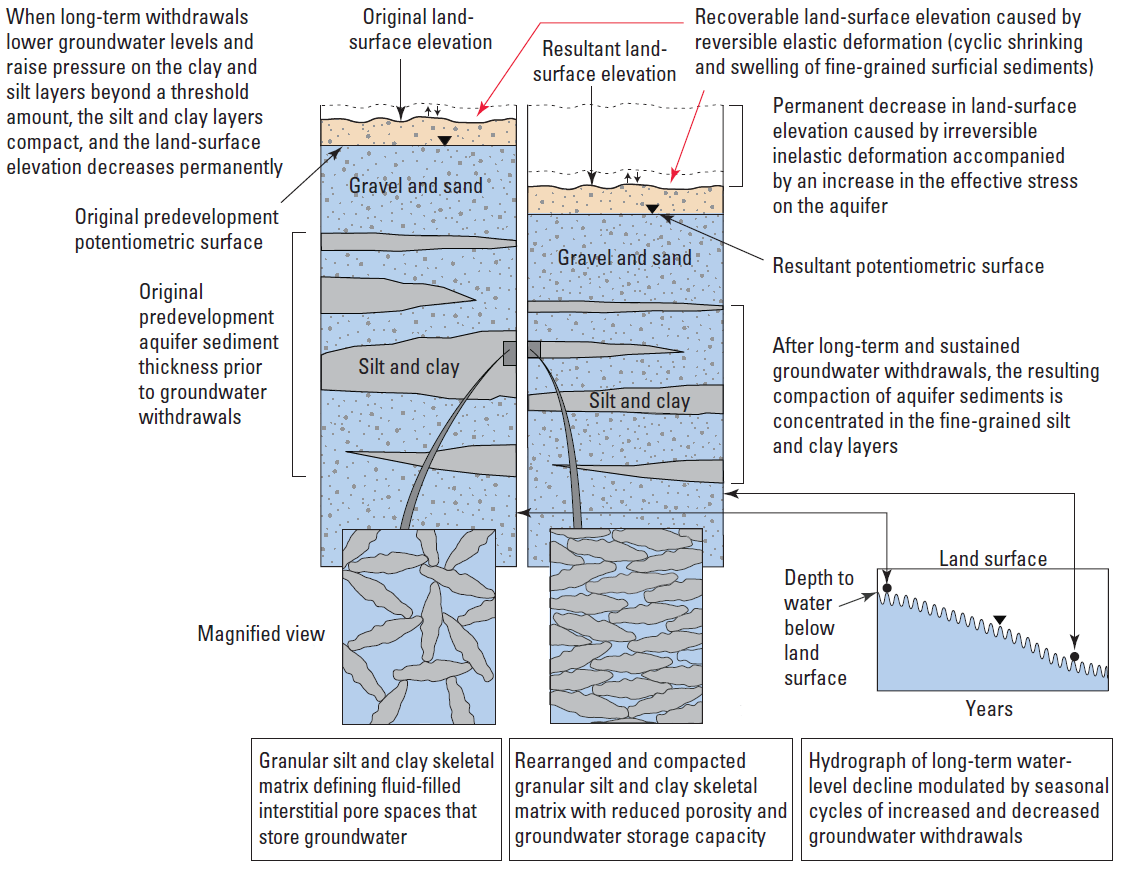

Land subsidence occurs when large amounts of groundwater have been excessively withdrawn from an aquifer. The clay layers within the aquifer compact and settle, resulting in lowering the ground surface in the area from which the groundwater is being pumped.

Subsidence articles and documents

HGSD 2023 Annual Groundwater Report info sheet

HGSD Subsidence Brochure 2023

That Sinking Feeling

If Subsidence is left unchecked

Preventing further subsidence in the Houston Area with Surface Water Conversion

Preventing Further Subsidence in the Houston Area with Surface Water Conversion

The information below is provided by the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District.

Significant issues with subsidence in the Houston area have been documented as early as 1918 when the Goose Creek Oil Field near Galveston Bay began to display surficial fissures caused by oil and water extraction beneath the surface. Subsequently, extensive research on local subsidence has confirmed a correlation between groundwater withdrawal and subsidence.

In 1975, the Texas Legislature created the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District (HGSD), the first political subdivision of its kind in the United States, to serve as a groundwater regulatory agency to prevent future subsidence.

HGSD has taken a reasonable and inclusive approach to groundwater regulation, water conservation education, and science and research programs resulting in reduced subsidence rates within Harris, Galveston, and surrounding counties.

Groundwater is not an infinite resource, and the best way to combat the consequences of excessive withdrawals is to account for future water demands and utilize alternative water sources. An alternative water supply assessment has been completed as part of Harris-Galveston Subsidence District and Fort Bend Subsidence District’s ongoing Joint Regulatory Plan Review. It provides an evaluation of alternative water supply strategies, including treated surface water, aquifer storage and recovery strategies, brackish groundwater development, and seawater desalination. The best strategy to prevent aquifer water-level decline, decrease in municipal supply well yields, and reduce subsidence is to diminish our reliance on groundwater and utilize alternative sources for water demand.

Earth fissure at Goose Creek Oil Field, near Baytown, TX, 1926

Historic image of water well and subsidence

The Importance of Surface Water Conversion

It is crucial to diversify our water sources to prevent further water-level declines in our aquifers. Surface water development involves the construction of new reservoirs, inter-basin transfer of available water supplies, and utilization of appropriated but undeveloped water supplies requiring extensive planning, permitting, inter-agency coordination, and infrastructure construction. The development of regional surface water supplies is relatively cost-effective due to their high yields, accessibility, higher water quality, and lower treatment costs compared to other alternatives.

A major benefit of surface water reservoirs is that they capitalize on existing natural water supplies by storing water and allowing for its use during higher demand periods when natural streamflow may not provide adequate supply.

Visit hgsubsidence.org for more information regarding subsidence, groundwater regulation, planning, research, and more.

Subsidence FAQs

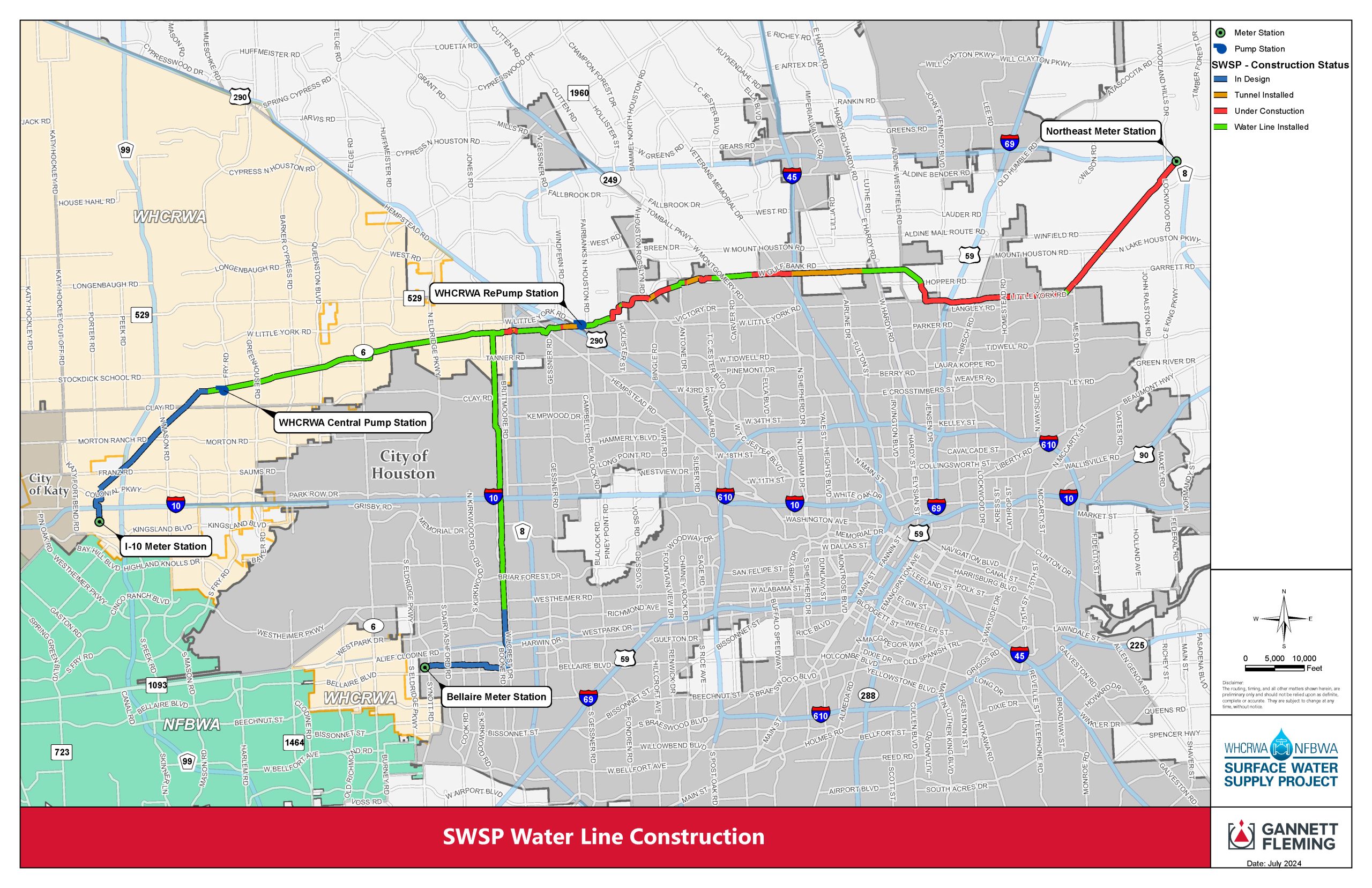

The Surface Water Supply Project (SWSP) will help to reduce land subsidence and will meet the water needs of a rapidly growing population. In compliance with mandates issued by the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District, and to meet water demands for 2025 and beyond, the WHCRWA is delivering the SWSP. The project also will allow the North Fort Bend Water Authority (NFBWA) to comply with Fort Bend Subsidence District groundwater reduction requirements.

Once complete, surface water from Lake Houston will be supplied to retail water providers (MUDs, PUDs, WCIDs, etc.) in the WHCRWA and NFBWA by way of the City of Houston’s Northeast Water Purification Plant through over 60 miles of pipeline and two large pump stations. These transmission pipelines will vary in diameter from 96 inches to 42 inches, depending on the pipeline segment. Construction of the entire project is expected to take place from 2020 to 2025 and will be completed in segments. In other words, the waterline will be constructed one piece at a time. For additional information, please visit the Surface Water Supply Project website http://www.surfacewatersupplyproject.com.

The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District is allowed to charge a “disincentive permit fee” to water providers that do not meet surface water conversion deadlines, which are: 1) Convert to 30 percent non-groundwater use by 2010; 2) Convert to 60 percent non-groundwater use by 2025; and, 3) Convert to 80 percent non-groundwater use by 2035.

The current disincentive fee (as of Jan. 1, 2025) is $12.12 per 1,000 gallons of well water pumped. In other words, if a MUD or water authority does not meet the conversion requirements each year, it is charged $11.86 per 1,000 gallons of well water pumped over the amount allowed until it meets the requirement. This could end up being an extremely expensive proposition.

There are several potential consequences of not moving to surface water, including additional land subsidence, which could lead to the failure of groundwater wells and increased risk of flooding in the areas that subside.

Prior to the 1970s, the majority of the Houston-Galveston region’s water supply came from wells that pumped water from underground sources, and that was taking its toll on the land that homes and businesses were built on. As the water underneath was drawn down, the ground above began to compact and sink – or subside – into the empty space where water was once stored naturally.

The most startling example of subsidence in the Houston region was the sinking of the Brownwood neighborhood near the Houston Ship Channel. Between 1943 and 1973, about 4,700 square miles of land southeast of downtown Houston sank at least six inches, with the area near the Ship Channel and Brownwood sinking about nine feet. Because it happened slowly, many did not realize its full effect until people’s homes began flooding regularly. Some structures were swallowed by the bay, and those that survived eventually were declared uninhabitable after Hurricane Alicia completed the devastation in 1983.

In 1975, the Texas Legislature created the Harris Galveston Subsidence District to regulate groundwater usage in Harris and Galveston counties to prevent additional land subsidence. After the District’s success in arresting subsidence southeast of Houston by regulating groundwater pumping, Harris County water providers were also required to seriously cut back on pumping groundwater from wells and to replace it with surface water, such as that from lakes and rivers. Failure to comply with the Subsidence District mandates triggers payment of “disincentive fees,” which are increasingly steep penalties.

Residents in west Harris County have traditionally relied on groundwater pumped from individual wells by municipal utility districts or other water suppliers. Not many people realized that there was a growing problem with land subsidence in their area, or that aquifers supplying the region were beginning to decline. Few noticed when — in the early 1970’s — just 50 miles south an entire subdivision was overwhelmed by flooding and sank into the marsh.

The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District — created by the Texas Legislature to “end subsidence” — was armed with the power to restrict groundwater withdrawals. The District issued its first groundwater regulatory plan in 1976, prompting industries on the Houston Ship Channel to convert to surface water supplied from the recently completed Lake Livingston reservoir. As a result, subsidence in the Baytown-Pasadena area was dramatically improved, and has since been largely halted.

Illustration of subsidence in a Gulf Coast aquifer as a result of groundwater withdrawals producing a decrease in the potentiometric surface (the groundwater level). Source: Kasmarek, M.C., Ramage, J.K., and Johnson, M.R., 2016, Water-level altitudes 2016 and water-level changes in the Chicot, Evangeline, and Jasper aquifers and compaction 1973–2015 in the Chicot and Evangeline aquifers, Houston-Galveston region, Texas: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3365, pamphlet, 16 sheets, scale 1:100,000, http://dx.doi.org/10.3133/sim3365.

Subsidence comparison of Brownwood Subdivision

Use the divider in the middle of the photos to the right to compare Brownwood from 1944 to 2002

The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District (Subsidence District or HGSD) was created by the Texas Legislature in 1975 as the first entity of its kind in the U.S. with the power to restrict groundwater withdrawals and prevent subsidence. Initially, the Subsidence District addressed the severe subsidence occurring in the Baytown-Pasadena-Galveston area — where whole subdivisions had to be abandoned after sinking below sea level — by requiring industries on the Houston Ship Channel to convert to surface water. The results were dramatic — subsidence in the Baytown-Pasadena area was significantly improved, and has since been largely halted altogether. Next, the municipal utility districts (MUDs), cities and private well owners in north and west parts of Harris County were told that they must use 80 percent surface water by 2035.

As it grew increasingly clear in the latter part of the 20th Century that the Houston-Galveston region needed to reduce its dependence on groundwater, the City of Houston started deactivating its water wells and building water treatment plants that could purify surface water from lakes and rivers.

The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District — a special purpose district created by the Texas Legislature in 1975, the first of its kind in the U.S. – was authorized to “end subsidence” and was armed with the power to restrict groundwater withdrawals. After the City of Houston converted areas along the Houston Ship Channel to surface water supplied from the recently completed Lake Livingston reservoir, subsidence in the Baytown-Pasadena area was dramatically improved and has since been largely halted. But as subsidence was stabilizing in the coastal areas, groundwater levels in inland areas north and west of the City of Houston were rapidly declining.

The Harris-Galveston Subsidence District’s goal was to achieve the same improvements in west and north Harris County so water providers were told to seriously cut back on pumping groundwater from wells and to replace it with surface water. The Subsidence District set deadlines: 1) Convert to 30 percent non-groundwater water use by 2010; 2) Convert to 60 percent non-groundwater water use by 2025; and, 3) Convert to 80 percent non-groundwater use by 2035. Failure to reach these goals would trigger payment of steep penalties.

Until the 21st Century, most residents who lived in Harris County, but outside of the City of Houston city limits, got their water from wells tapping into underground aquifers. This water has been delivered to homes and businesses by hundreds of individual MUDs and when the faucets were turned on…water came out. People were blissfully unaware that the aquifers that had provided what seemed like an endless supply of drinking water were beginning to decline. We are moving to surface water because the underground water supply we have traditionally relied on is shrinking.

In addition, as the county has grown, the underground water has become so depleted in some areas that the ground above it has begun to sink, a process known as subsidence.

The West Authority was created by the Texas Legislature in 2001 to facilitate the shift from pumping underground well water to surface water supply (water from lakes and rivers) by municipal utility districts (MUDs) in west Harris County, and the City of Katy. When large sections of Harris County – primarily to the north and west of the City of Houston – were directed by the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District to convert to 80 percent surface water supply over the next 20 years, there was no centralized government that could take on the task of negotiating and securing a long term supply of water from the City of Houston or other entities that had surface water to sell. Harris County did not have the right to own, operate and sell water, so it was up to the municipal utility districts to figure out how they would do it on their own. It was a monumental task for the individual MUDs, so four large water authorities – the West Harris County Regional Water Authority, North Harris County Regional Water Authority, Central Harris County Regional Water Authority, and the North Fort Bend Water Authority in Fort Bend County — were created to manage the supply challenge and to design and construct new water delivery systems for their respective areas.

Researchers Find ‘Significant Rates’ of Sinking Ground in Houston Suburbs

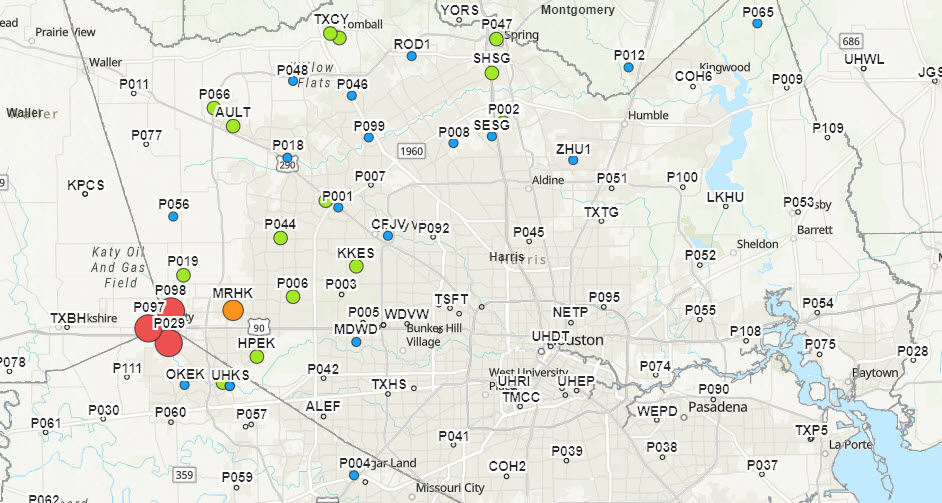

An analysis of thousands of water and oil wells in the Houston metro area has uncovered significant rates of subsidence, or gradual sinking of the ground, in some of the region’s fast-growing suburbs that have not been previously reported.

Shuhab Khan, professor of geology at the University of Houston, led the study published in the academic journal Remote Sensing. His team found substantial subsidence in Katy, Spring, The Woodlands, Fresno and Mont Belvieu with groundwater and oil and gas withdrawal identified as the primary cause.

“Subsidence used to be a rare phenomenon. Now, it is all over the world,” Khan said. “There are 200 locations in 34 countries where there’s known subsidence. Cities in the northern Gulf of Mexico, such as Houston, have experienced one of the fastest rates of subsidence.”

Severe subsidence not only raises the possibility of flooding homes and businesses, but it also produces a negative feedback loop, the study authors write. The weight of floodwater from severe flooding can compress the sediments in the subsurface and could exacerbate the already compacted soil to potentially drive subsidence further.

The researchers used interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR) data obtained from a European Space Agency satellite, which showed total subsidence of up to 9 cm to the north, northwest and west of Houston from 2016 to 2020. The subsidence rate was 2 cm a year.

Khan and his team applied optimized hot spot analysis, a statistical tool, to groundwater level data collected over the past 31 years from more than 71,000 water wells to consider how much groundwater pumping contributed to subsidence. Similarly, they used the same analysis on more than 5,000 oil and gas wells to evaluate their impact on subsidence.

“It is thanks to the latest advances in geospatial analysis that we were able to investigate subsidence across the Houston area in unprecedented detail,” said Otto Gadea, a graduate student from Khan’s team. “By analyzing comprehensive datasets from recent years, we determined for the suburbs, excessive groundwater extraction appears to be the primary driver of subsidence. Meanwhile for other areas such as Mont Belvieu, subsidence can be attributed to the heavy withdrawal of local oil and natural gas reserves.”

With population growth, groundwater extraction has become more prevalent in the Houston area. Khan points out downtown Houston, suburbs to Houston’s southeast and parts of Spring Branch previously experienced subsidence, but because of groundwater regulation, the subsidence is no longer substantial.

His team also studied natural causes for the sinking, like the expansion and shrinking of Houston’s clay, silty and sandy soil sediments, and the impact of flooding. Sinking may also be causing fault movement in the area.

“If current ground pumping trends continue, faults in Katy and The Woodlands will likely become reactivated and increase in activity over time,” the authors write.